The following essay will seem to be about a quite unreal and fanciful state of affairs, like that of an alternative or parallel universe. That is because it was written 25 or more years ago, before the possibility it recognises in its last but one paragraph had become a reality, when universities hadn’t yet become unis and before anyone had glimpsed the possibility of their members being ‘cancelled’ for any number of forms of wrong-speak. It is about, if not a parallel universe, then one that is superseded and lost—become, in a phrase of F. R. Leavis’s, forgotten and incredible. So, wherever it says “the university is …”, understand “the university was …” or “the university has or had been …”.

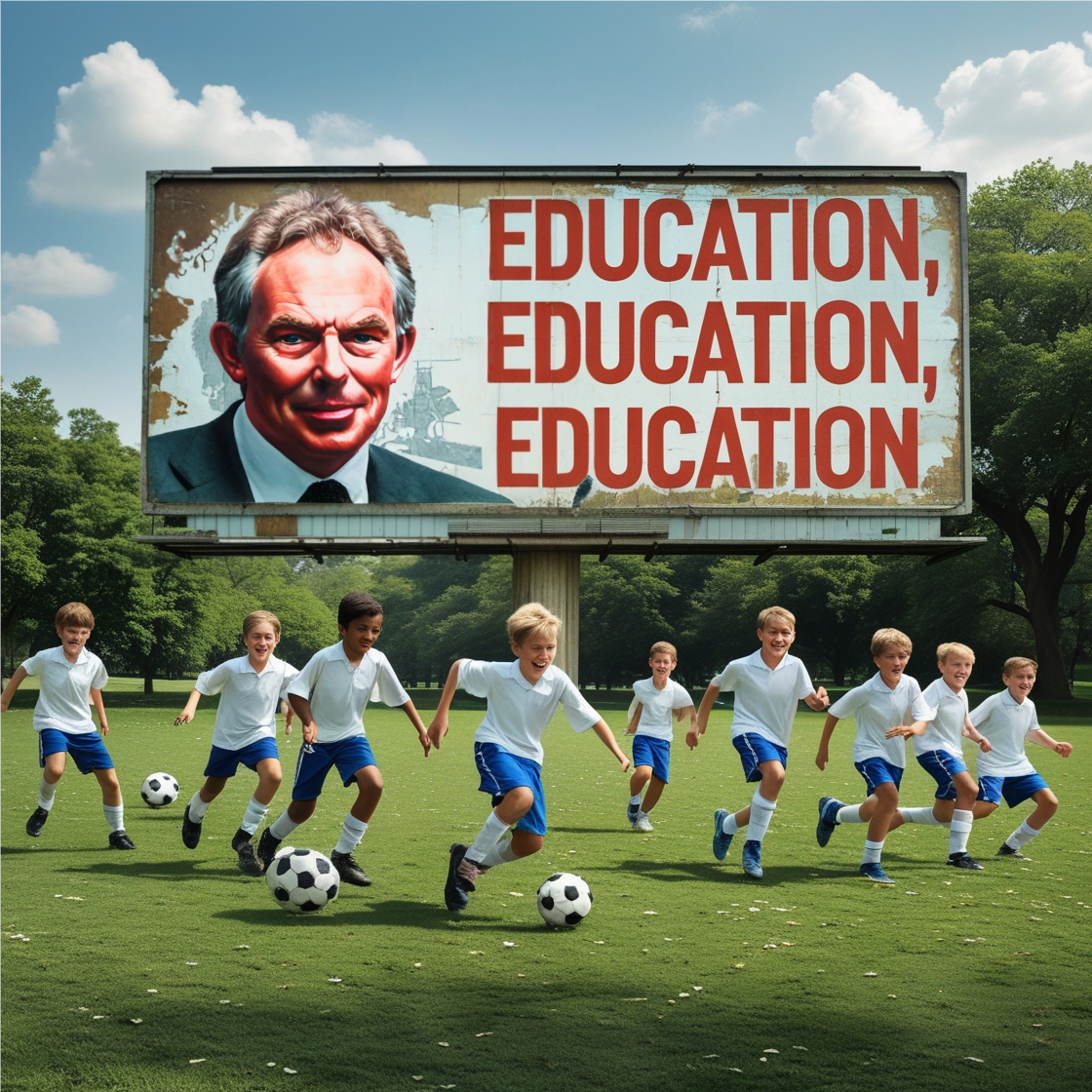

New Labour has recently uncovered a new social problem: that too few working class go to the better universities. It has named the problem “Access”, as if the working class were all in wheelchairs and the universities didn’t have the ramps for them. But in thinking of the matter as a problem, for which, of course, there must be some administrative solution waiting to be discovered, New Labour betrays that it understands neither the working class nor the university.

“Some universities . . . send out the message that only certain types of people are welcome,” Charles Clarke complains. The Daily Telegraph objects (April 9th) but not on the grounds that the universities would be right if they did but—conceding that they would be wrong—on the grounds merely that the charge is unfounded, the evidence “anecdotal”. But, on the factual point, Clarke is right: the range of types welcomed by universities is limited. There are those who fall outside it—who place themselves outside it by being unwilling or unable to accept the invitation the university makes. Universities—while they remain universities—do welcome only certain types of people and would be wrong if they didn’t. If some universities don’t welcome some types (and not all would welcome every education secretary we’ve had in recent years—not, let’s hope, on their staffs at least), all that that means is that some are trying to remain universities in fact while others are content just with the name (and the funds).

The former don’t need to apologise to Charles Clarke, though, for the narrowness of the range of human types they welcome. They welcome, as it happens, a much greater range than, say, the Houses of Parliament or the BBC or PricewaterhouseCoopers. The outspoken and outrightly rebellious have a freedom to speak out and rebel in universities that they have scarcely anywhere else. The university is an institution (the Church, not co-incidentally, is another) in which authority follows only very approximately the hierarchy of seniority, title and point on the pay-scale.

It is one of the very great and serious attractions of university life that in it the junior is free to insult or otherwise lay the law down to the senior as he is almost nowhere else. Where else but in a university would that hierarchy, faced with a Wittgenstein or a Nietzsche, flatten itself so readily? (Where else would David Starkie have got on so happily? New Labour?) The worst penalty facing the outsider is slow or no preferment. Not much of a penalty, really, and with its own compensations too. University life is naturally, intrinsically, competitive, and the race—the everyday race in the common room, lab and committee room and before the students—does not always go to seniority. Leavis, for practically his whole career at Cambridge, was junior but who had the essential authority in his department, the kind of authority all university teachers crave? Who, when he spoke, was listened to? Was it E. V. Lucas? Or Tillyard? Outsiders often call the university an ivory tower. Inside, it more often seems a bear pit. Which is why civility has always been prized and cultivated there: for fear of what would happen if it weren’t. Universities give a very wide latitude not just to the rebellious, the eccentric, the impolite and the immoral but even to the clinically insane. Where else but in a university would the schizophrenic mathematician John Nash have been welcome? Or the manic-depressive psychiatrist Kay Redfield Jamison?

But, of course, neither Clarke nor the Telegraph leader writer is interested in whether universities welcome types like these or not. Their argument is about class. The subject here is class—and nothing else. And what the two sides agree on is that all classes ought to be equally welcome and that for universities to discriminate against the working class would be shockingly wrong. Of course, there is one way of taking that in which it is obviously true but there is another in which it is—ought to be—just as obviously false. Although it isn’t very often said publicly, everybody knows it to be true that, for the working class, being educated means in very important respects being educated out of their class. (And once out, who wants to go back, even if it were possible?) Within certain limits people can be trained with systematic reliability. They can’t be so educated at all, not within any limits. Education makes an invitation—which can always be refused. And for anyone from the working class the invitation is an invitation to leave behind not merely a “background” but a self. It’s an invitation to see, think, feel, judge differently (which is why there can be no going back). It’s an invitation to become—in Charles Clarke’s phrase—a different “type of person”, which makes it an invitation easy to refuse. And if it is refused, it is refused; and there’s an end of it. The university is classless only in ideal conception. Its values are ones anybody, from any class, might uphold but in practice, in our world, if it is to survive at all, it is necessarily dominated by the educated—that is, the middle and upper—classes, and just as necessarily discriminates against those of the working class who can’t or won’t accept the invitation it makes. It wouldn’t be a university if it didn’t.

Of course, Clarke, being New Labour, doesn’t use the term “working class”; he prefers terms like “disadvantaged” which make the user sound more of a charity worker and less of a socialist. But, for the user, this new term may have risks too. Firstly, “disadvantaged” is a lot like “disabled” in suggesting that those it applies to have no distinctive character of their own but must be defined solely in terms of where they fall short of others. But the meaning of “working class” isn’t “lacking the advantages of the middle and upper classes”—not to the working class it isn’t—though it was to Bloomsbury and is to Charles Clarke. It isn’t like having only one leg when other people have two. (And that New Labour holds its working class supporters in unconscious contempt is already starting to be apparent to them and in the long run may prove more damaging to its political fortunes than any present dislike of a humbled Conservative Party is to its.)

And then if you can’t see working class life as a form of life with a distinctive character of its own, with its own virtues and vices; if you can see it only as a sort of truncated middle class life—middle class life with bits lopped off—you’re never going to understand the thing you profess to be concerned about, what the leader-writer calls “the low achievements and aspirations of working-class pupils”.

The first thing you need to be able to imagine is that working class people like their own way of life and aren’t typically eager to give it up for someone else’s—Mr Clarke’s, say, or E. M. Forster’s. Usually, understandably and often rightly people don’t want to be like some other set of people they have no connection with: they want to remain what they already are, and be like their relatives, neighbours, friends. They might want two Jags like Mr Prescott but only on the condition that they remain as much what they are as Mr Prescott has evidently remained what he was. What they don’t imagine is turning into Mr Cook or Mr Mandelson or, even, I would guess, Mr Kinnock. When George Eliot’s unimaginative squire in Silas Marner wants to adopt as a young woman a daughter he abandoned as a baby and who has been brought up by a weaver, she, to his astonishment, rebuffs him, saying, “I don’t want to be a lady—thank you all the same. I couldn’t give up the folks I’ve been used to. . . . I like the working-folks, and their victuals, and their ways.” (Not everyone feels like that all the time, of course. My father used to like to say—conscious of the irony—“I ’ate the workin’ class.”)

So what Mr Clarke and the Telegraph agree to call “poverty of aspiration” is something with more sides to it than any such phrase could ever suggest.

The suburban Essex grammar school I was at (Buckhurst Hill C.H.S., founded 1938; since 1989 the Guru Gobind Singh Khalsa College, had two distinct social catchments when I was there in the fifties—one, “local” and middle class, the other moved from bomb-damaged “slums” in East London to newly built council estates. All the pupils at the school had passed “the scholarship”, and there’s no reason to suppose that in 1950 the examination or its marking favoured the working class, or that the boys off the council estates who passed it were less clever than their middle class counterparts. Nevertheless, it was, predictably, the middle class boys who regularly did best in the yearly competitive examinations; so the “A” stream was predominantly middle and the “C” stream predominantly working class. The sixth form was, of course, composed overwhelmingly of boys from the “A” stream. But going into it from a “C” stream didn’t seem to be a disadvantage. The boys there from the “A” stream, who all through school had got much better marks, did not seem to be cleverer or to know more in proportion as their marks had been higher. Without doubt lots of boys who had left school at 16 with “O” levels could profitably have stayed on into the sixth-form and gone on to university.

But what is the meaning of the fact that they didn’t? Perhaps it ought to be called as Charles Clarke and the Telegraph leader writer agree to call it, a case of “low achievement” and “poverty of aspiration”. But that wasn’t how it seemed to the “C” stream itself. There was a good deal about our suburban grammar school that suggested a socially transplanted public school: religious “Assemblies”, the “House” system, the school song, (from memory) “Fair set above the Roding stream/By wide and grassy leas/Our House stands fairly to the winds/’Twixt Essex lanes and trees . . .”, regular homework, regular competitive examinations, an elaborate system of punishments (including for offences committed on the way to and from school, such as, for example, not wearing an identifying school cap), prefects (with powers of punishment and their own common room), a staircase for sixth-formers only, school uniform (colours those of the first Head’s Oxford college), teachers’ gowns, compulsory cross-country, cricket and football matches that were all friendlies, outside any league . . . . This was all alien to the council estate; and however else it might be construed, it could hardly not be construed as an invitation (or something more pressing) to undertake a kind of social migration, not just to take a different path from that of one’s parents but to make oneself a different type from them. The school presented the council estate with an opportunity, made it an invitation which, it was hardly surprising, the council estate, on the whole, preferred not to take. But who can be sure it was so very wrong? To see this not at all in the light of Eppie’s loyalty to where she belongs but merely as “poverty of aspiration” . . . is to be even more stupidly unimaginative than George Eliot’s squire. It comes from the habit of looking at these things as statistics only and as “social problems”, without catching any glimpse of the persons involved. Is this a habit of the educated? (If it is, what could better vindicate the council estate’s preference?)

There was an incident in about my third or fourth year which made it clear not only that the council estate did prefer its own to the school’s but that it was capable of giving the school lessons on the subject. The school had become dissatisfied with the turn-out for after-school House football matches. Players were being selected but sloping off home instead, so that games were regularly having to be played without full teams. It was letting team-mates down, letting the House down and showing a kind of disrespect for the school as a whole. And to show how seriously the matter was being taken, in future, boys who wouldn’t play for their House team on school days would not be permitted to play for the school teams at weekends.

At which threat, the council estate first sniggered, then laughed outright, then clapped and cheered. What did the school think? That they wanted to play for its teams, rather than their own, with their mates? Did it imagine it counted for something in their lives? Or as anything but a set of demands they found insolent, arbitrary and incomprehensible? Didn’t it know? Apparently not.

Of course, education doesn’t have to take the precise form it took at Buckhurst Hill C.H.S. in suburban Essex between 1950 and 1958 (good though I believe it was). And there are, no doubt, forms it could take which would make it more attractive to the council estate. It might perhaps have done more, in more cases, to bend itself to the estate rather than the estate to itself (though, in my own case, I must record, that it could, in co-operation with my parents, scarcely have done more). Nevertheless, if it’s education—not another thing, training, say—that the estate is being offered, there are things about the estate that have to be left behind, on it, if the offer is to be taken up. A change of character—of type of person—is, for good or ill, a necessary part of what’s on offer. It’s a common joke to say, “You can take X out of Mile End/Newbiggin/Salford. You can’t take Mile End/Newbiggn/Salford out of X.” But that is precisely what education does try to do, to take out of X what there is of Mile End, Newbiggin and Salford that is incompatible with itself.

And if the joke likens education to a rough sort of surgery, well, it can be that too, and, like surgery, go wrong or leave scars. Among other things education has the power to do is damage. Africa must be full of people educated out of tribal society but not into any other, left stranded. And who hasn’t seen the similar power Oxbridge can have? Surgery’s all very well but you don’t want to lose too much or the wrong bits. You do want to come out intact.

One glimpse of what there might be in working class life that’s incompatible with education can be had at just about any park football match. It’s not so much that, whenever, for example, the ball goes out of play, players from both sides claim to the referee that it’s “their ball”. It’s a bit more that they routinely do so even when they know perfectly well that it isn’t. And it’s a bit more still that there isn’t a footballer in the country at any level capable of feeling any shame at doing so. (Kenny Dalglish can utter the sporting equivalent of “Never give a sucker an even break” in front of several million people, and not even that nice Gary Lineker thinks he’s said anything remarkable.)

But what I think really is something is the unconscious parody of disinterestedness players from time to time put on. Several times in every game—when the referee awards a foul perhaps—players will raise their hands above their heads and clap the referee, pointedly, even earnestly. A stranger to the scene might, at first, think he was witnessing the behaviour of something like a jury, passing its own judgement on the verdict of a judge—applauding a right decision in a hard case. But he’d soon notice things to change his mind: that the applause came from all different parts of the pitch (including those remote from where the incident took place), that the opposing teams never clapped the same decisions and that the only decisions anybody ever clapped were those that went in their own favour. And amongst the supporters—one set on one side of the pitch, the other on the other—any sense of justice is, if anything, even less in evidence than amongst the players: while the game is in progress it is positively wrong, a disloyalty, to applaud the play of the other team; it would be like giving comfort to the enemy.

For it isn’t that these footballers and their supporters lack a morality but that they have a different one from that of the educated middle class. A virtue is being upheld here, a real one, which no conceivable form of human life could do without and which, in a crisis, may seem all-important to almost anyone: group solidarity or loyalty, surrendering oneself (including, unfortunately, one’s sense of justice) to the common cause. By talking, encouraging, calling out to one another (often it doesn’t matter what), all remind all that they’re a team and bound together. By exhorting and encouraging one another—especially when behind—you both show your heads haven’t gone down and keep them up. “We’ve gone quiet, lads” is a reproach and a reminder that games aren’t won by skill alone. To the educated spectator, clapping the referee only when he gives decisions in your favour may look like a parody of judgment; to those clapping and their supporters it is just part of everything that cements team solidarity and identity.

But, it has to admitted, whether genuinely a morality or not, it isn’t a very good preparation for university. It’s more a code than anything else, a shrunken version of the clan morality Alan Breck gives Davie Balfour a lesson in, in Kidnapped: “Hoot! the man’s a Whig, nae doubt; but I would never deny he was a good chieftain to his clan. And what would the clan think if there was a Campbell shot, and naebody hanged, and their own chief the Justice General? But I have often observed that you Low-country bodies have no clear idea of what’s right and wrong.”

Disinterestedness—the cardinal academic virtue—is (so I would say myself) markedly not a virtue much regarded, or regarded at all, in working class life. You stick up for yourself and your own, that’s your part and your duty. It’s a point of view from which disinterestedness and the wish to do justice look either like disloyalty or like simple-mindedness, the promptings of someone who doesn’t know either where his duty or where his interest lies. If pressed to say why he “’ated” the working class, my father would generally say, because they’d got no sense of justice, that in the army you might expect to get justice from an officer but not from an NCO, “one of your own”. And in that last phrase, one can see what is partial and untrustworthy in that working class virtue of sticking by your own: what if “your own” don’t recognise you? Being from the working class ought to be no barrier to university entrance, of course; being of it has to be.

New Labour—perhaps “the left” generally—seems to look on the human world as if it were something made from Lego, and composed of elements without any organic relation to one another. Taking this one example of the relation between university education and class alone, isn’t it obvious that the university is an invention of the higher social classes, with roots in the daily life of those classes which it just doesn’t have in the lives of the working class? The university is native to middle and upper class culture in a way that it just isn’t to working class culture. So, of course, a higher proportion of the former classes will go to university—rather as a higher proportion of the working class will be found playing football on Sunday morning in your local park. As long as the classes exist, the universities will be found to have a “bias” against the working class—rather like the bias water has to run downhill (or that football teams have against aristocrats). Before it can overcome it, New Labour will have to become Old Labour again and make the whole class system disappear. Until it does so, a vulgar (working class?) description of its attempts to “widen access” might be “pissing in the wind”.

There is, though, as far as the universities go, one way it might piss into the wind without soaking itself, and that is to re-make the university as an institution compatible with working class culture, that is, as one which trains instead of educates. And this, of course, New Labour (following the example of the Conservatives) is doing, systematically. We could call it “proletarianizing” the university, or, then again, we could call it destroying it.

The other thing we might do is buy back Buckhurst Hill C.H.S. from the Sikhs.