Trump eliminated the estate tax on farmers this week. This is a huge boost for their survival and the celebration in every township and county will go on for years. Also last week, the EPA eliminated the preposterous endangerment finding on CO2.

In April, Lee Zeldin launched the biggest deregulatory program in history, which means that rural America can now grow again after fifty years of deliberate, Club of Rome, suppression.

Zeldin’s actions will roll back trillions in regulatory costs and hidden taxes that have caused the cost of cars, homes, fuel and business operations to rise artificially. Much of that regulation was gold-plated fantasy, that financially benefited the regulators and ruined everyone else.

Further, given these regulatory reforms, starting businesses and manufacturing in local communities will be much, much, easier. This is huge. When I drove through rural America ten years ago, the men and women who made those counties run, lived in a kind of permanent despair. They were convinced they, their culture, traditions, history and towns were going to die within their lifetimes and, not only that, be maligned, buried and forgotten.

That is no longer true. But, and of course, there is a but, buried in Trump’s Genius Act, lies yet another fascist incursion on America’s lands. You have to be rich to care about land, otherwise your life is too fraught with getting by to even think about it. But property is everything, and Canada and the US have billions of acres from which to make bank by and for the conscienceless rich.

Jim Rickards, a WarRoom regular, and savant, suggests that Trump plans to monetize it all, but who gets that money? A one-time payout to …who? Public debt? After which it is alienated from Americans, and Wall Street owns and trades it. Which means the international set. The Worst People On Earth.

The Genius Act institutes yet another government program meant to measure the “assets” on public land and monetize them through “scientific investigation”. This is just another excuse for land taking. Search federal lands through this. These programs never end well. They are top down, careerist and managed behind the scenes by careless ideologues.

Here is a brief, yet salient description of how it happens and who and what it ruins. Oligarchs and bureaucrats try to turn into a machine something living that only country people understand. Country people that they inevitably treat like dirt. And ruin. Thereby ruining the land, water, traditional culture, and the root of our humanity. Not to mention our food and our water.

The War on Farmers prosecuted by the WEF/UN/EU/NGO/DeepState consortium of thieves helped propel Trump into office, but MAGA started in the American heartland, long before Trump found it and lit it on fire. The fight of the people who feed, clothe and house us is absolutely fundamental to our well-being. When the land they tend, enhance and help to produce is being aggregated into some idiots wealth fund, it means ruination; it is as destructive as AI run amok.

Trump’s legacy, if it includes more misery for rural America, will be poisoned.

“Listen for the frailty.”

That was the order that John Sawhill, past president of New York University, then head of the Nature Conservancy, gave to thousands of youthful operatives in the 1990s. Sent into rural communities, they were to find a way to acquire an asset—a river, a wetland, a fertile valley, or a forest—that the Conservancy wanted. Join clubs, volunteer, help out, be a neighbor, play with their kids. And listen for the frailty.

But many times, that valley or forest wasn’t all they wanted. When Harry Reid wanted the water of the Lahontan Valley for Las Vegas, the only way he could get it was through John Sawhill, who sent Graham Chisholm, now the executive director of Audubon California, to buy those rights. Chisholm’s master’s thesis was on the development of the Green Party in Germany, and in the five years he spent romancing the citizens of the Lahontan, Chisholm demonstrated the iron fist cloaked in Robin Hood suede of “the largest environmental organization in the world.”

Chisholm arrived just after the 101st Congress, in the last act of its last session, delivered to Harry Reid something he’d been after for a very long time. “The Settlement Act gave Reid the right to “settle” the dispute between California and Nevada about the water splitting off the west and south flanks of the Sierra Nevada. The Lahontan Valley was the site of Teddy Roosevelt’s first western reclamation project in 1906, when he promised to “make the desert bloom.” Ranchers and farmers had vested water rights in the valley that went even further back than 1905. But as soon as the act was signed, Lahontan Valley farmers were beset by fresh regulatory demands and lawsuits. Since they had endured seven years of drought, the regulations meant that many families were teetering on the edge of survival—which is exactly where Reid and TNC wanted them.

Here’s the thing about country people. They live by the rhythms of nature; some years some crops flourish and others don’t. There may be long periods of drought or too much rain. Or too much cold. Or heat. You have to be able to turn on a dime and grab opportunities before they vanish. You do not have time to purchase a permit, hire registered environmental professionals to do a study, and then wait for months, if not years, for bureaucrats a thousand miles away to give you permission. You start a business, make some money, end it in eight months, and start another. You sell a hunk of land one year and buy it back the next or ten years later. You shear off an acreage for a child who wants to farm or ranch or to build a house for an aging parent. You build shacks for seasonal workers that are in use for ten years, then tear them down or use them for WWOOF (Willing Workers on Organic Farms) or agritourists or a straightforward motel for resource workers because a mine or gas field has been opened in the area. You make your living from a half-dozen different sources, and pretty much every year, the sources change. Regulation that controls everything from the height and footprint of a barn, creek setbacks, and the number of outbuildings to the number of people you can employ, how you must pay them, the depth and flow of your irrigation system, and the dust and noise you can raise make life pretty close to unmanageable.

But for Chisholm and the Lahontan Valley, the first years were a honeymoon. Thrilled to have a young, educated kid move into the valley, especially one with such starry connections, residents treated Chisholm like a celebrity. He did not disappoint; according to Findley, he joined everything. He volunteered with the Ag Center’s committee testing local wells in the drought. He organized a new group to defend local water rights. He was at the meetings of the irrigation district and the county commission. He was at the melon festival and the county fair. This kind of behavior is duplicated in all 3,300 counties in the United States, where agents of TNC or any one of a proliferation of foundations or ENGOs work to determine the future of the community. On my islands, activists from Montana, Los Angeles, New Jersey, and a half-dozen other states moved here and now chair a dozen political action committees, all of which produce hysterical reports based on “science” about our collapsing ecosystems. Our Salt Spring activists are in their creaky eighties; the island is more like a retirement camp for successful environmental activists than a place where the young can earn their stripes. But in any region, you can tell who they are by the causes they espouse and the issues they press: water, first and always, then affordable housing, the saving of whatever natural feature dominates the region and of course the sleeper, climate mitigation.

Well-educated, well-spoken, and always talking about “the community,” before a marina or hotel or an organic fair-trade coffee-roasting facility can be built they insist on “studies” that will cost the public purse in excess of $100,000 and take five years. I have not found, in a decade of searching, one authentically rural region to which they have not brought decline.

Or disaster. By the time Graham Chisholm left the Lahontan Valley, it was already trending toward dust and tumbleweed, the houses abandoned and useless without a working ranch surrounding them. And the people found they’d lost their purpose as well; without the connection to the land they’d had so long, they didn’t really want to live. As Timothy Findley of Range Magazine began his story on the fate of the irrigators at Harry Reid’s hands, one rancher, the day after signing all the papers that transferred the rights to his ranch to the Nature Conservancy went out on his back porch, a check in his pocket that meant he could live anywhere he wanted, and shot himself. Perhaps he had cancer; perhaps his wife had just left him; there was no note. The salient facts remain. He had just received more money than he’d ever had or even dreamed of, but he didn’t want to live. Wherever you go in ranching country, similar stories proliferate. Mostly, people work so hard at staying, at conforming to the mitigations, regulations, hearings, lawsuits foisted upon them, they fall ill.

It all sounded so good. Going in, Chisholm and TNC claimed they merely wanted to “restore” 25,000 acres of wetland on the Carson River, ignoring the fact that the Lahontan farmers had kept it as a duck preserve for decades. But it was win-win. Chisholm’s offer meant they could keep the marsh and get some badly needed money. Given the drought and regulatory compliance costs, community leaders admitted that there had to be some additional sacrifice going forward. Marginal lands would have to be sold. Chisholm offered to buy them for the Nature Conservancy. The head of the irrigation district was the first, then a leading family and so it went. Children sold their heritage, more interested in the money than a lifetime of brutally hard work and uncertainty. But the lands weren’t bought at their appraised or fair value, because only the water rights were being sold. It seemed fair enough to the desperate. As is typical in this game, once the water rights were gone, anyone left was forced to sell at a considerable discount; TNC had effectively reduced the value of Lahontan Valley land to virtually nil. Said the last holdout, seventy-five-year-old cowboy poet Georgie Sicking, “I had no choice, really. They bought everything around me, including the irrigation ditch.”

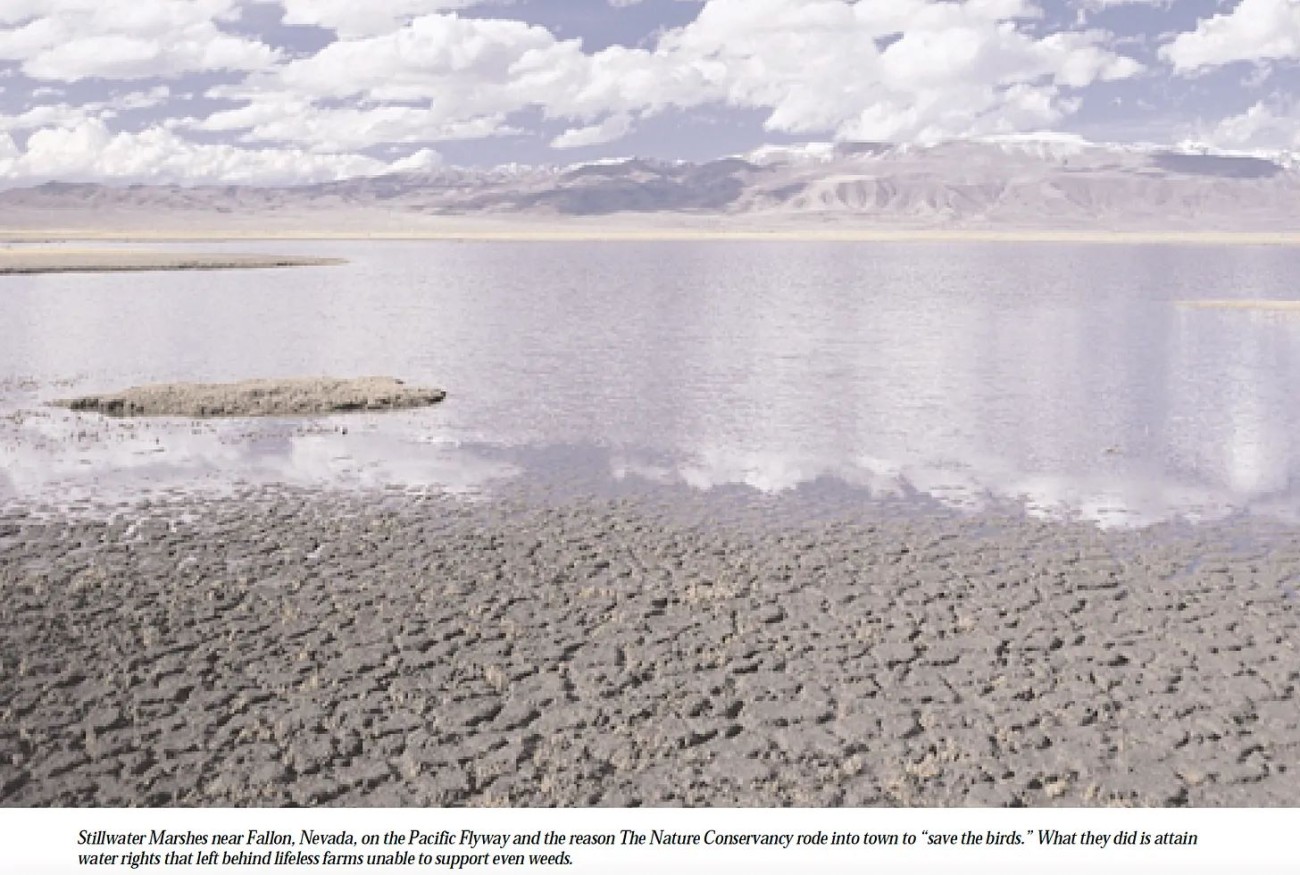

But Chisholm got his marsh “save” and a promotion to director of the wealthiest chapter of the Nature Conservancy in California. He was praised and celebrated and today is acclaimed for “saving” countless “treasures,” with no mention of the ruination in his wake. But by the time of his promotion, the affection for Chisholm in the Lahontan Valley community was long dead, especially when they discovered that Chisholm had been operating under a memorandum of agreement between TNC and the Fish and Wildlife Service to buy the water rights and shift them to the government, leaving, as Tim Findley put it, “ghost farms and pale, lifeless fields of laser-leveled ground unable even to support the growth of weeds.”

Needless to say, Harry Reid got his water. And rather than the abundant nature touted in its nature porn, the desertified Lahontan Valley is a more typical Nature Conservancy gift to the future.

This must not happen again.