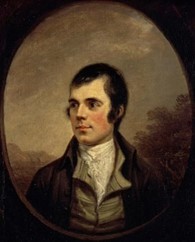

I don’t know how old I was when I first became aware of who Robert Burns had been, but he has been all around me almost from the moment of my birth. Being Scottish, well, mostly Scottish (72%, 25% Irish with a dash of English), it couldn’t really have been any other way. I couldn’t say his songs and poetry filled the house, but my grandmother used to sing ‘Ye Banks and Braes’ alternately with ‘I Love a Lassie’ or ‘The Bonnie Banks o’ Loch Lomond’. There was a tartan-bound book of the complete works of Burns on the bookshelves in the corner of the sitting room, although I don’t remember ever taking it down to read until I was in my mid-teens. Nonetheless, my early life was peppered with songs and phrases from many sides which I would later realise came from the pen of one man.

At school he took hold. There was no escape. In English lessons Burns’ poetry commanded as much attention as did Chaucer, Shakespeare, Scott and Dickens. We learned ‘The Twa Dugs’, ‘Address to Edinburgh’, ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’, ‘To a Mouse’ and, of course, ‘Tam O’Shanter’. In music lessons we were back to ‘Ye Banks and Braes’ (Actually the Banks o’ Doon), added ‘A Man’s a Man for A’ That’, ‘Johnnie Cope’, ‘Ye Jacobites by Name’, and ‘A Red, Red Rose’, which is possibly the greatest love song ever, and a few others besides.

In 1960s Scotland there was a burgeoning Scottish Folk scene largely driven by the Corries, Roy Williamson and Ronnie Brown. Those of us who tried to strum a guitar enhanced our Burns repertoire at the local Folk Club where we sang Burns’ songs made popular once more by Roy and Ronnie, especially those referencing significant events in Scottish history - ‘Scots Wha’ Hae,’ (the Bruce’s address to his army before Bannockburn) ‘Killiekrankie’ (the battle of Killiekrankie, a Jacobite victory in the first Jacobite rebellion in 1689) and ‘Parcel o’ Rogues’ (a lament for the Act of Union). Talented as they were as exponents of Burns’ songs, however, it was Roy and Ronnie who wrote and left us that frightful dirge ‘Flower of Scotland’ which has taken hold as a national anthem when many think an upbeat version of ‘Scots Wha’ Hae’ would be far better.

Back to Burns. To Burns Suppers in fact. At my all-boys school in Edinburgh, once we got to the senior years, we would get together with the senior years at the nearby girls’ school which, incidentally, was the one which had been the model for Muriel Spark’s Marcia Blane School for Girls in ‘The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie’. Those among us who were genuinely musical would do a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta once a year, but the main event was the joint Burns Supper which was our initiation into the annual Burns rituals in which we celebrated the life and work of the Ayrshire ploughman poet as we tucked into haggis, neeps and tatties. ‘Neeps’, for you Sassenachs, are swedes which we call turnips in Scotland. Our first Burns Suppers were somewhat curtailed events, being wound up by the supervising teachers around 9 pm (school tomorrow) and, naturally, there was no whisky. These defects would be addressed later when I attended Burns Suppers at university and beyond, even performing on one occasion.

Burns’ father William strongly desired that his children should be educated and ‘Rabbie’, the eldest of seven, went to school for just two and a half years in Alloway before continuing his education at home with his father, alternating with work on the family farm. Realising his own limitations, William managed to persuade his neighbours to join with him in employing a young tutor, John Murdoch. Murdoch held his lessons in their various farmsteads and, under him, Burns learned English, French, mathematics and received a good grounding in Latin. He became a voracious reader of both novels and more learned works as well as the Bible. However, with the family resided old Betty Davidson, a beacon of ignorance, credulity and superstition who bequeathed to the young Rabbie a large collection of country tales and songs concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, deadlights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, enchanted towers, dragons and other folklore. So, you can see where ‘Tam O’ Shanter’ came from.

This dichotomy of learning versus superstition is crucial to appreciating how a peasant lad from the poorest of beginnings could become the most popular poet of his or any other time, not only in Scotland but around the world.

But there’s a third facet. Burns’ generous and enthusiastic love of life - and his life of love. This was, after all, a man who fathered twelve children by five different women (some say ‘at least’ 13 children) and packed it all into a life that would last just 37 years. Burns was a founder member of the Tarbolton Bachelors’ Club, and we may like to think he would have had more than a little hand in devising its Rule X:

“Every man, proper for a member of this Society, must have a frank, honest, open heart, above anything dirty or mean, and must be a professed lover of one or more of the female sex. No haughty, self-conceited person, who looks upon himself as superior to the rest of the club; and especially no mean-spirited worldly mortal, whose only will is to heap up money, shall, upon any pretence whatsoever, be admitted”.

No-one could ever say that Burns even once infringed Rule X in the course of his short life. His work bears witness to a “frank, honest and open heart” and there is no doubting his love for several of the fairer sex, Jean Armour above all. As a far as the filthy lucre is concerned, his education allowed this author of ‘Parcel o’ Rogues’ to become an exciseman and collect revenues for the British Crown in his latter years which is a sign that he never achieved any great wealth through his poetry and song. He wasn’t really comfortable in this role, an unpopular job, even writing a derogatory song about it, ‘The Deil’s Awa Wi’ Th’ Exciseman’.

Perhaps his greatest achievement is his almost single-handed revival of a large part of the Scottish folk-song traditions which might, in another time, have earned him a substantial financial reward. True to his beliefs, he never accepted a penny, despite its being offered, for what was as far as he was concerned, a labour of love.

Now, I won’t be at a Burns Supper tonight and nor, I suspect, will many of you, dear readers. I had thought of trawling YouTube to find the best elements of the order of proceedings, the best speeches at a Burns Supper, to construct our own within this piece starting with the Selkirk Grace and going right through the Piping in of the Haggis and the Address, The Immortal Memory, the Address tae the Lassies and the Lassies’ Reply and a recital of ‘Tam O’ Shanter’. It traditionally ends with the singing of ‘Auld Lang Syne’, the second most often sung song in the world after ‘Happy Birthday’, which might, or might not, actually be the end depending on whether or not a ceilidh band has been organised. It wouldn’t work though. To be honest an awful lot of the videos I viewed weren’t very good; besides, if you’ve already clicked on the other links above, it would make this celebratory piece a bit too long overall.

So instead, I’ll confine it to the best Address tae a Haggis and the best Immortal Memory speech I could find. Both are delivered by one Cameron Goodall who seems to make a bit of a profession of doing this sort of thing. They’re not just speeches, they’re performances. Hint: Access to a dictionary of the 18th Century Scots dialect may be a handy thing to have. Enjoy them.

After a glorious repast it’s time for the Immortal Memory.

But that’s not all. No Burns Supper is complete without a recital of ‘Tam O’Shanter’ so here’s the Scottish actor James Cosmo delivering one of the best.