Eighty-four years ago today, on Sunday 15th September 1940, the German Luftwaffe launched its largest and most concentrated attacks against London with the aim of drawing Fighter Command of the Royal Air Force into a battle of annihilation. Around 1,500 aircraft took part in the air battles which lasted until dusk and the action was the climax of the Battle of Britain. September 15th is ‘Battle of Britain Day’ and each year it is marked to commemorate the day in 1940 when the Luftwaffe attacked the outnumbered Fighter Command with all the might it could muster.

After the fall of France there had been a hiatus which allowed the Luftwaffe to recoup its losses despite which, buoyed by its victories, its spirit remained good. Nevertheless, it had been forced to wait until its strength had been rebuilt to acceptable levels before a main assault against the RAF could be made.

The Luftwaffe’s campaign had been going on for some two months since Hitler gave the Wehrmacht Directive No 16 that ordered preparations for the invasion of Britain. Unternehmen Seelöwe (Operation Sea Lion) required air superiority or air supremacy over the Channel and Southern England. The Luftwaffe was to destroy the RAF to prevent it from attacking the invasion fleet or providing protection for the Royal Navy's Home Fleet, which might otherwise prove to be an insurmountable obstacle to a successful invasion attempt.

The first phase of the German air offensive was in the English Channel. The Kanalkampf ("Channel battle") rarely involved attacks against RAF airfields inland. Instead, the aim was to provoke RAF squadrons to engage in battle by attacking British Channel convoys. The shipping losses inflicted were minimal and so was the impact on Fighter Command. It had lost 74 fighter pilots killed or missing and 48 wounded in July, but its overall strength had risen to 1,429 pilots by 3 August although it was still under manned.

The second phase, which spread the raids to coastal airfields, radar and stations just south of London, occurred between 8th and 18th August. Luftwaffe bombers also bombed industrial and dockland targets as far north as Liverpool during night hours. The first major raid inland and against RAF airfields came on 12th August. RAF Hawkinge, Lympne, Manston and radar stations at Pevensey, Rye and Dover were attacked along with Portsmouth docks.The results were mixed. The Radar station at Ventnor on the Isle of Wight was badly damaged and others targeted were also damaged, but not destroyed. All were in working order by the following morning. A certain amount of luck played its part in that German intelligence failures led to many targeting errors. For example, airfields not belonging to Fighter Command were attacked along with non-operational radar training establishments.

The essential target was Fighter Command. Its destruction would deny Britain air superiority. Throughout July and early August, the Germans prepared for ‘Adlertag’ (Eagle Day), the first day of Adlerangriff (Operation Eagle Attack) a full-frontal assault on Fighter Command airfields. Göring had promised Hitler that Adlerangriff would achieve the results required within days, or at worst weeks. In fact, the Luftwaffe had so far not achieved success commensurate with its effort. Nevertheless, in the belief that it was effectively degrading Fighter Command, it prepared to launch an all-out assault on the RAF. By 12th August, German air strength had reached acceptable levels. The Adlertag assault had been postponed because of bad weather but it was eventually carried out on 13th August 1940. The German attacks on that day inflicted significant damage and casualties on the ground, but again marred by poor intelligence and communication, they did not make a significant impression on Fighter Command's ability to defend Britain.

The Luftwaffe’s campaign continued for the next month. The German High Command had planned to issue new orders for Operation Sealion to be launched on September 17th, so control of the skies was vital if an invasion plan was to proceed. On September 14th, Göring gave the order that an all-out aerial assault was to be made on the RAF in southern England on September 15th.

The Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command, and architect of Britain’s air defences, was Air Chief Marshall Sir Hugh Dowding. Perhaps a more important and influential commander was the New Zealander, Air Vice-Marshall Keith Park, the Officer Commanding 11 group which was charged with the defence of London and the South-East. British intelligence had already picked up and informed Park that a large attack by the Luftwaffe was to be expected. The date was unknown, but they were certain that it would be soon. Park’s 11 Group was expected to bear the brunt of the attack and Park had done all he could to make it as effective as was possible given the rates of attrition it had been sustaining.

To compound Park’s difficulties, relations were strained with his fellow Group Commander at 12 Group to the North of London, Trafford Leigh-Mallory. Leigh-Mallory, who had some senior backing, favoured the ‘Big Wing’ tactic in which three or more squadrons would link up in the air before joining the battle. Park felt this was unwieldy, that the ‘Big Wings’ took too long to assemble, and they arrived too late, often after the bombers had attacked. He wanted Leigh-Mallory’s group to defend 11 Group airfields while his own squadrons were engaging the enemy as far out as possible, and he felt that 12 Group was failing him.

While at breakfast on the morning of September 15th, Park was informed of a large build-up of Luftwaffe forces along the French coast. He concluded that this was the start of the huge raid he had been warned about. The weather was clear, and this helped both the Luftwaffe and Fighter Command. While the Luftwaffe had no clouds to cover its approach, its bomber crews and fighter escorts would more easily be able to see incoming waves of Fighter Command’s Spitfires and Hurricanes.

This was the day that Winston Churchill had chosen to visit Fighter Command at 11 Group’s headquarters in Uxbridge and Park escorted the Prime Minister and his wife to his bombproof command centre fifty feet underground. Park was informed of a very large build-up of Luftwaffe aircraft near Dieppe and Calais. He brought Biggin Hill, Hornchurch and Kenley up to ‘stand by’ and when it became clear that the size of the incoming force was far greater than initially thought, the rest of 11 Group. At 09.30 two large Luftwaffe forces approached the southeast coast but then turned back to France - a feint aimed at drawing Fighter Command into the air too early.

At 10.30 another large Luftwaffe force was detected gathering between Calais and Boulogne. However, the sheer size of the force meant that it took a long time to form up, putting pressure on the fuel reserves of its escorting fighters. This gave Park time; 11 Group was again ordered to ‘stand by’. It was at this time that Park told Churchill that a “big one” was expected. By 11.00 it was clear from radar that a very large bomber force was approaching with an unknown number of fighter escorts, and they were estimated to cross the coastline at Dungeness at 11.45.

Between 11.05 and 11.20 twelve fighter squadrons were scrambled – 4 Spitfire and 8 Hurricane. They faced a very large Luftwaffe force that was two miles across and flying between 15,000 and 26,000 feet. Among the bombers were Me-110 twin-engined fighters while flying above the whole force were the covering Me-109s. The size of the incoming force was such that Park ordered part of 12 Group to scramble. Between 11.35 and 11.40 a further eleven squadrons took to the air – 4 Spitfire and 7 Hurricane. In total Fighter Command had 23 squadrons in the air.

As the Luftwaffe force crossed Kent, 11 squadrons from Fighter Command intercepted it with 12 held further back in reserve or used to protect London from the incoming bombers. The nearer the Luftwaffe bombers got to London, the more squadrons from Fighter Command joined in. Many of the Me-109 escorts had to turn back as they were getting low on fuel, and this made the bomber force easy prey to the Spitfires and Hurricanes. Many Luftwaffe bombers dropped their bombs randomly to lighten their load, facilitating defensive manoeuvres, and make a speedier return to occupied France and Belgium.

However, the day was not over for Fighter Command. They had fought the first of two huge waves. While the first Luftwaffe wave returned in disarray, the ground crews of Fighter Command had to rearm and refuel their aircraft in readiness for another attack. At 13.30, radar picked up another large Luftwaffe force massing off Calais – 150 bombers escorted by 400 fighters. They were expected to cross the English coastline at 14.15. The ground crews had done their job, as every squadron that had fought in the morning was ready again by 14.00. Shortly afterwards, 20 squadrons were in the air. It was clear that the Luftwaffe’s target was again London. This time the incoming raiders were spread across a ten-mile front. Faced with a ferocious RAF onslaught, many German bombers once again dropped their bombs at random and the intended target – docks in the East End – received just minimal damage.

Throughout that day, Fighter Command had been forced to use absolutely everything at its disposal to counter the two huge main attacks launched by the Luftwaffe; by its end, the threat had been repelled. While the Battle of Britain continued until the end of October, the Luftwaffe’s spear had been turned and blunted. There would be no German control of the skies over Southern England or the English Channel; Operation Sealion was postponed indefinitely.

That night the British public was informed by the Air Ministry that Fighter Command had shot down 183 German aircraft. The real figure was 56 but the damage to the Luftwaffe was more than just lost aircraft. Göring had told his men that Fighter Command was down to its last fifty Spitfires. In fact, they had faced over 250 fighters. While it is difficult to measure a drop in morale, there can have been little doubt that in the minds of the men at the sharp end of the Luftwaffe that Fighter Command was a formidable opponent. On the day, Fighter Command had lost 26 aircraft with 13 pilots killed.

In the aftermath, Dowding retired, and Park was replaced by Leigh-Mallory whose views had been supported by the Deputy Chief of the Air Staff, Sholto Douglas. Both Dowding and Park were somewhat shabbily treated by the Air Ministry. Today, however, it is Dowding and Park who have statues in their memory, not Douglas and Leigh-Mallory.

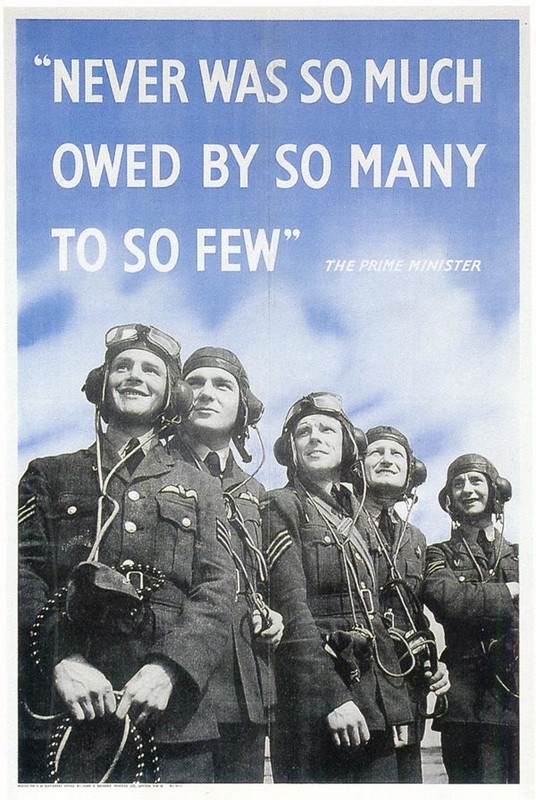

And what of the young men who did the air fighting? While there was a hard core of experienced pilots as flight and squadron commanders, none would ever have seen anything like the fast-moving, terrifying, air battles of 1940. Many were still boys, not long out of school, flung into battle while still learning to master their Spitfires or Hurricanes. And they were all volunteers. Not all were British. There were Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, South Africans, Irishmen from the Republic, even a smattering of Americans volunteered. And, of course, there was the Polish 303 Squadron who were perhaps the fiercest fighters of all.

The memoirs of Geoffrey Wellum in his book First Light tells the story from his joining the RAF at age 17 in 1939, through his training, to his flying and fighting in the Battle of Britain as the youngest Spitfire pilot of 92 Squadron.

They were all undoubtedly warriors but there was one thing which drew them to it - the sheer exhilaration of flying and having at their fingertips the power of a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. The feeling is perfectly captured by the quintessential airman’s poem High Flight, written by John Gillespie Magee Jnr, a Spitfire pilot of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

High Flight

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I've climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds,—and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov'ring there,

I've chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air ....

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I've topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark nor ever eagle flew—

And, while with silent lifting mind I've trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

Pilot Officer John Magee went through his training just a year too late to take part in the Battle of Britain. He was killed aged 19 a few weeks after he wrote this poem when he bailed out too low for his parachute to open following a mid-air collision.

They are all gone now, those young heroes of 1940. We shall not see their like again.