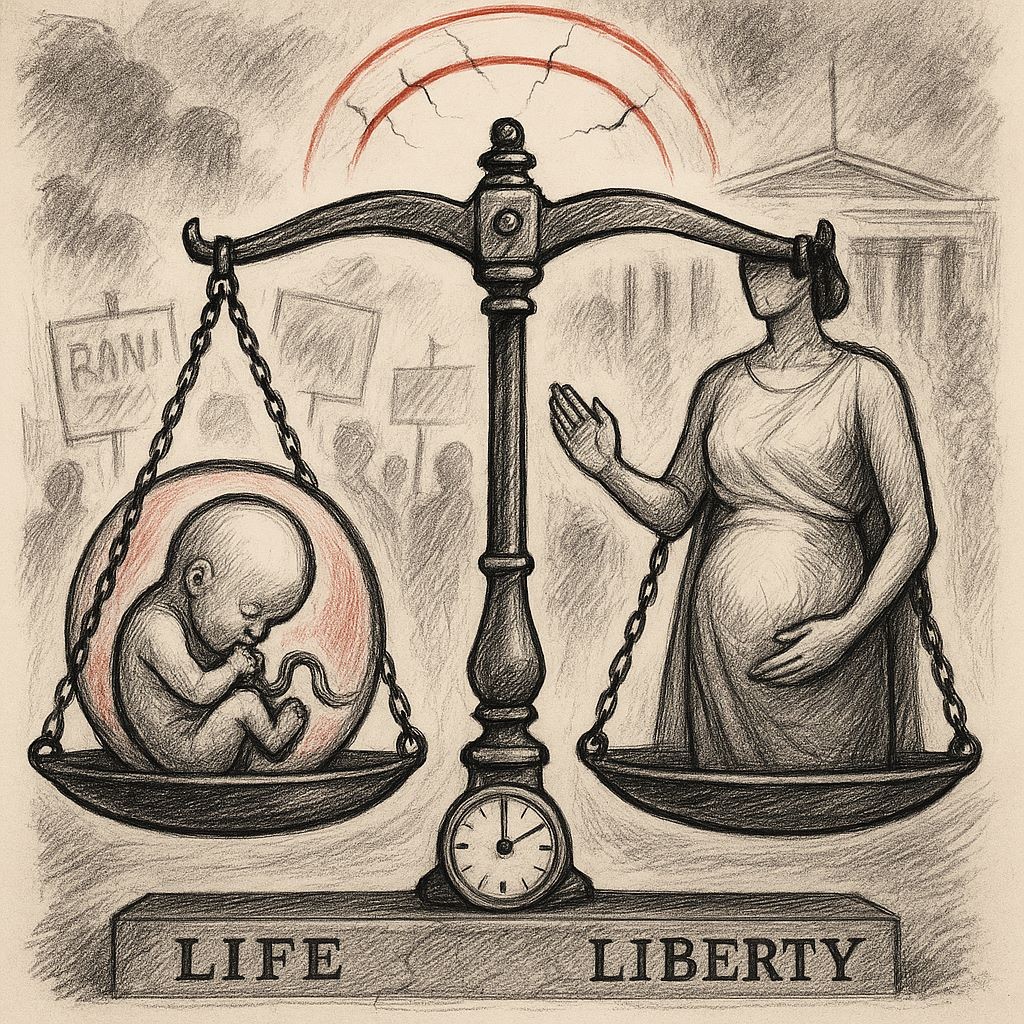

In the enduring and often painful debate on abortion, two moral titans clash: the sanctity of human life and the sovereignty of individual liberty. This is not simply a contest of political ideology, religious conviction, or gender politics, though it includes all these dimensions. At its core, the abortion debate is a confrontation between first principles: the belief that human life is inviolable and begins at conception, and the belief that personal freedom, including a woman’s right to control her own body, is paramount.

These two highly important basic principles appear, to me at least, to be in irreconcilable opposition when it comes to abortion. And yet, the persistence of the debate, its stubborn resistance to compromise and its frequent dissolution into partisan shouting matches, and the leftist Establishment’s efforts to impose what many see as extreme legal settlements, suggests that both principles contain moral truths that demand our attention.

I have been unable to square the circle myself. Instinctively I’m repelled by the idea of abortion, but equally desirous to preserve individual freedom. I even doubt whether abortion should be a matter for government at all, but pursuing this idea leads into a mental and moral quagmire, so let’s leave it be.

This essay seeks, therefore, not to assert one principle over the other, but to engage them both dialectically so far as I’m able: thesis, then antithesis to try to get a reasonable synthesis, to explore their tensions, challenge their limits, and search, if possible, for a synthesis that honours both the complexity of human life and moral responsibility. It is also an invitation to those on both sides of the argument to reason together and help me where, inevitably, I have failed to achieve a satisfactory synthesis between the two matters of basic principle.

So, let’s start with the case for ‘life’ and the moral gravity of conception. The pro-life position begins with a powerful moral intuition: that human life, however small or undeveloped, is sacred. If we accept that the embryo, from the moment of conception, contains the full genetic blueprint of a human being and has the natural trajectory to become one, then it is not a mere biological artifact. It is a nascent human life.

For many, this belief is not simply, or only, rooted in religious doctrine but in a consistent ethic of humanity. The embryo may be minuscule and insensate, but so too are the earliest moments of every human existence. To end that life deliberately is seen not just as a private decision but as a moral rupture: the taking of a human life, an act that has a significant impact on the wider society and is fundamentally wrong.

Philosophers such as Robert George and Patrick Lee argue that what matters morally is not what we can do i.e. consciousness, reason, sentience, but what we are: members of the human family. A being does not become human by acquiring functions; rather, it develops those capacities because it already is human.

There is, too, a slippery slope concern. If we begin to assign moral worth based on developmental stage, we enter dangerous territory. Where do we draw the line? Viability? Neurological activity? Self-awareness? Any such criterion is inherently arbitrary and invites broader relativism: toward the elderly, the disabled, the comatose. Once life’s value becomes contingent, no life is ultimately secure, surely a major concern in today’s dystopian society, where the elderly were sacrificed on the evil altars of covid and the NHS.

To me, the above is a compelling argument, but what about the second principle, the case for liberty, autonomy, privacy, and the right to choose? In equally compelling moral terms, the pro-choice argument centres not on what the foetus is, but on what the woman is: a fully autonomous person, capable of reason, agency, and self-determination. And her autonomy, the argument goes, must include control over her own body including the no small matter as to whether to carry a pregnancy to term.

No other person, however needy, has the legal or moral right to use another’s body for sustenance. We cannot be compelled to donate organs or blood, even to save lives. To force a woman to remain pregnant against her will, with all the physical, emotional, and existential consequences that entails, is to treat her not as an autonomous agent, but as a vessel.

For many women, especially those facing poverty, violence, or limited access to healthcare, the inability to terminate a pregnancy can have life-altering consequences. In such cases, abortion is not a matter of convenience; it is a question of survival, dignity, and equality. To outlaw abortion is, effectively, to outsource the cost of moral purity to women’s bodies, disproportionately those of the vulnerable.

Moreover, this perspective recognises that society is pluralistic. People disagree — often deeply — about when life begins, what counts as a person, and what our obligations are to the unborn. In such a context, imposing a single moral vision through law becomes not just problematic, but unjust. A free society must allow space for moral disagreement and for individual conscience.

The heart of the abortion dilemma, I’m beginning to think, lies not in choosing which principle is more important, but in acknowledging that both principles carry moral weight. The foetus is not nothing. It is a living, developing human organism. But neither is a woman’s body a public resource, to be conscripted by the state or any form of morality in the service of that life.

Many attempts to resolve this tension collapse into absolutism, even bigotry: abortion is either murder, always and everywhere, or it is a private medical decision, akin to having a mole removed. But both of these positions distort the moral landscape. Abortion is neither mere homicide nor mere inconvenience. It is a morally abhorrent act, because it involves the ending of nascent human life. But it is also a morally defensible act, because it involves the preservation of a woman’s freedom, health, and future.

What, then, does a synthesis look like? Remarkably like common sense, it seems. They way I see it is that we should start from the premise that moral status is not binary, but analogue, gradational if you like. I know, it’s an ugly word, but all I can think of. Not all lives are equal in every context, and not all stages of life carry the same moral weight. A fertilised egg is not a conscious being; a foetus at six weeks does not feel pain or have preferences; a foetus at twenty-four weeks may. Morality, like biology, develops in stages, at least in regard to such a complex moral dilemma as abortion.

This suggests that the moral permissibility of abortion should depend on gestational age. Early abortions, in the first trimester (up to the end of the 13th week of pregnancy), when the foetus is most undeveloped, may reasonably be ethically permissible with fewer restrictions. As the pregnancy progresses, the moral burden increases, and the conditions under which abortion is permitted more morally onerous and so should become more stringent. As some pregnancies don't show until about 20 weeks, and as by 22 weeks survival is possible, it seems reasonable to conclude that 20-22 weeks should be the time from which no further intervention should be legal, except in life threatening circumstances.

Such a framework is not hypothetical. Versions of it are already law in many democracies. Formerly in the U.S. under Roe v. Wade, and in much of Western Europe today, abortion is broadly legal in the first trimester, subject to regulation in the second, and restricted in the third except in cases of serious medical need.

This structure reflects an ethical equilibrium. It respects the developing life of the foetus, without treating it as morally absolute from conception. It upholds a woman’s right to choose, while recognizing that the scope of that right may narrow as the foetus acquires greater moral status.

To take the argument further leads into more moral ambiguity and, in my view, away from both first principles. On researching this article I’ve seen it argued several times that a morally coherent abortion policy must be accompanied by social and economic conditions that support women in choosing to carry pregnancies to term, if they wish to. It is not enough to say, “choose life” they say, we must make life choosable, by providing universal access to contraception, maternal healthcare, childcare, housing, and income support. In other words, we move away from personal autonomy and responsibility towards Big State intervention, nay domination.

It can be said that a society that restricts abortion without supporting motherhood engages in moral hypocrisy. It demands sacrifice without solidarity. Conversely, a society that permits abortion but ignores the reasons women seek it, such as poverty, fear, lack of support, fails to fully understand freedom seriously. Reproductive justice, as many feminist thinkers argue, means not just the right to avoid pregnancy, but the right to raise children in safety and dignity. But that all too often is a call for more socialism, an idea that has only ever resulted in mass poverty or worse, mass murder.

To me, we must reject all attempts to drag the subject of abortion into the wider cultural wars and stick to first principles. Abortion is a moral problem not because it is simple, but because it is not. It forces us to weigh two sacred things — life and liberty — against each other. To choose one and ignore the other is not principled clarity; it is in my view an ethical evasion.

The path forward lies, in my opinion, in resisting the pull of ideological certainty and not pushing dubious fashionable ideologies to their logical limit, but instead in respecting the complexity of the issue and crafting laws and norms that reflect both moral seriousness and human compassion. Such a path will not satisfy the purists on either side. But perhaps moral maturity requires that we stop seeking purity and start seeking justice, real justice that protects both the unborn and the born, that honours life without diminishing liberty, and that trusts individuals to make decisions of conscience within a framework of shared ethical responsibility. This is not a compromise of principle. It is a principle in its own right.

So, in conclusion, having groped my way through the moral maze, I think that abortion on reasonable grounds up to about 20-22 weeks should allowable, and liberally allowed on a sliding scale diminishing in permissibility from 13 weeks. But after that, the grounds for abortion should be made very tight, and abortion only allowed for very serious reasons such as a serious risk to the mother’s health. After 20-22 weeks, and here my medical knowledge runs out, I can see there being hardly any valid reasons, we can never say there will be none, but only the most very serious reasons for aborting the child.

It will follow therefore, that I find the British governments spatchcocked new laws on abortion not only immoral, but also ludicrous: doctors will not be legally allowed to carry out abortions in the third trimester, but mothers will be legally allowed to DIY abortions. My mind finds the whole idea grotesquely wrong and deeply immoral.

It is hard for me to see any redeeming grace in this hideous new legislation, in fact, I’m beginning to think that the British Government is part of a sinister Death Cult, a subject that will be taken up on a planned essay on the equally deadly, equally abhorrent, equally immoral – and possibly related - ‘assisted dying’ bill.