In these VE Day celebrations, genuine and mixed with propaganda and nonsense, most will appreciate the sacrifices made by British servicemen (and women) in WW2. Deserved praise will be heaped on the Army, the Royal Navy and the Royal Airforce. But I wonder how many will spare a thought for Poor Jack, the forgotten, almost exclusively working-class, Merchant Seaman, without whom the war could not have been won?

The first British casualties of the war occurred just hours after it was declared, when Athenia was torpedoed by U-30 on 3rd September 1939, resulting in the loss of 112 lives. No phoney war at sea. The last casualties of the war with Germany were also at sea, when Avondale Park was torpedoed by U-2336 on 7 May 1945, while negotiations were being completed for Germany's unconditional surrender the next day.

Throughout the war Britain had by far the largest merchant fleet, making up over a third of the world’s merchant ships. Around 150,000 men, all civilians, served at sea in the British Merchant Navy in WW2. Most sources record 30,258 dead and 4,654 missing, or around 35,000 killed. In addition, another 15,000 non-British crew died, Indian, Pakistani, Yemeni and Chinese. That is a higher casualty rate than the Army, the Royal Navy and the Royal Airforce (though individual units within those forces, like commando units and Bomber Command, had higher). Approximately 2,828 British merchant ships were sunk, amounting to around 14.7 million gross tons - well over a ship a day. For 2,194 days.

In his Second World War history ‘Their Finest Hour’, Churchill admitted that the U-boat threat to the shipping lanes of the Atlantic was the only thing that really frightened him during the war. He did not exaggerate, as without supremacy at sea, it is likely that the war would have been lost (and yes, the Soviets relied heavily, especially in the beginning, on material given to them by Britain, Canada and the US).

Often overlooked in the grand narratives of military strategy and battlefield heroics, the steadfast and courageous British merchant seamen’s contributions were invaluable to the war effort. The Merchant Navy was the lifeblood of Britain's supply chain, ensuring that food, fuel, and essential war materials reached our shores. Their voyages were fraught with peril, as they faced the constant threat of enemy submarines, surface raiders, and aircraft. Despite these dangers, they persevered, driven by a sense of duty and a commitment to their country.

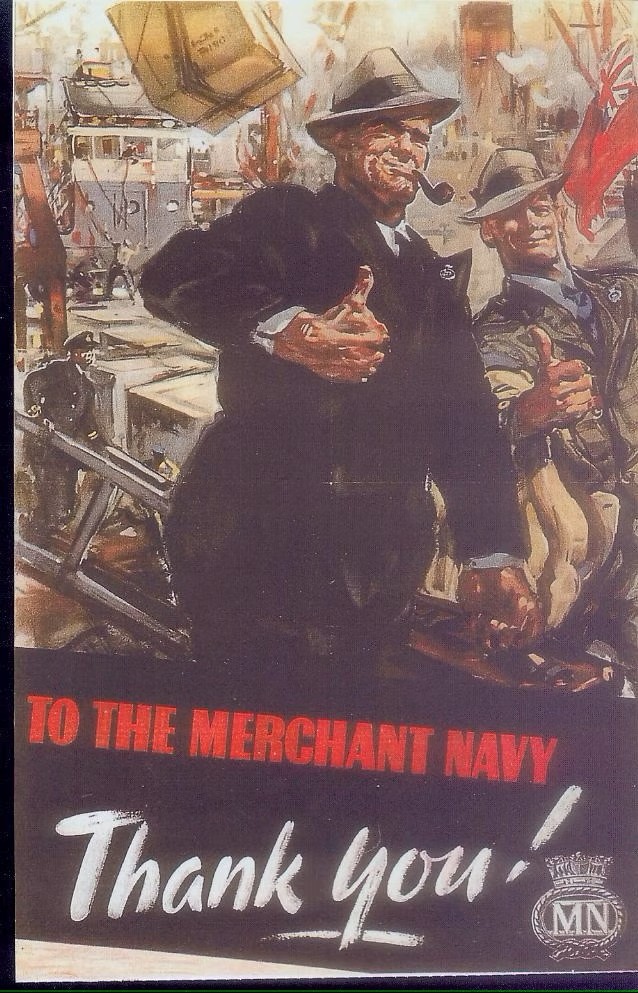

And, officially, a bit, their country remembers them and honours their courage and dedication. Those few who know anything about them recognise that they, ordinary men who did extraordinary things, embody the spirit of determination and resolve that has (or was) long been a hallmark of the British character. Their legacy is one of quiet heroism and unwavering service, and for that, we owe them our deepest gratitude.

Now, the Red Ensign flies at the Cenotaph, and the few remaining old salts march with, no, behind, the Royal Navy.

But official recognition took a long time. The Merchant Navy was not included in the official Remembrance Day parade until 2000, and even then, only after a long campaign by the Merchant Navy Association, and against fierce opposition from the MoD and, I’m told, the Royal British Legion. A Merchant Navy Medal was introduced, and a Merchant Navy Day, 3 September, were initiated in the same year. Few have heard of it.

When I first went to sea almost all the senior officers, the Captains and Chief Engineers, had served in the MN during the war. My first Chief Engineer, an old Tyneside terror, had gone to sea in WW1 as a twelve-year-old, and thought nothing of using his fists against stroppy apprentices.

After a while, I became aware of a deep-rooted sense of bitterness in these men. Many felt betrayed, their sacrifices ignored, and their dead shipmates forgotten. And I gradually learned that, during the war, they were often treated abominably. Many had taken to wearing their MN badge upside down, ‘NW’ to stand for not wanted.

At first, I didn’t believe the stories I heard from these old men. But then I asked family members who had been at sea during the war, and found it was all true. Living conditions on many ships were atrocious. Bedding was bare planks, and seamen joined a ship carrying a ‘donkey’s breakfast’, a sack cloth bag stuffed with straw which served as a mattress.

Food was often abysmal, and strictly rationed, and many Captains refused to buy fresh fruit and vegetables. Even in my day it was often horrible, and I’m still suspicious of anything with a French name: cauliflower au gratin meant that the cauliflower had gone bad and had to be covered with melted cheese to make it edible. Seamen rated a shipping company by its reputation for feeding. One company, Hogarths of Glasgow for example, was notoriously bad, and known to seamen as Hungry Hogarths.

The pay was poor compared to the pay received by a factory worker ashore and working hours much longer. The merchant seaman had a basic working week of 64 hours before overtime was earned, compared with 44 hours ashore. Considerable resentment was felt by seamen after learning that men of the U.S. Merchant Marine earned more than double their wages. And for much of the war they received no leave pay. This changed later, after much agitation, when the Ministry of War Transport reluctantly agreed to pay seamen a less than generous two days paid leave for every month served at sea.

The same ministry, however, compensated ship owners handsomely for ships lost due to enemy action.

And then there was the enemy.

U-boats mostly, but also aircraft and the occasional surface ship like Tirpitz. On a slow convoy of eight knots (9.2 mph) it would take almost sixteen ½ days from New York to Liverpool and almost thirtytwo days from Buenos Aries to Southampton. The U-boat could strike anywhere, anytime, without warning. You could be in your bunk warming the donkey’s breakfast, working on deck or on watch in the engine room, from where, if a torpedo struck the ship in way of the machinery spaces, the chances of escape were slim. But an engineer kept his watch there, four on, eight off, every day at sea, day after day, seven days a week.

No wonder Jack was often a nuisance ashore, but he received precious little sympathy from the authorities.

The type of ship and its cargo made a major difference to survival rates. One of the most dangerous cargoes was iron ore, which because of its weight would cause a ship to break up and sink in seconds – yes seconds – if a torpedo struck and cargo holds were flooded. A man caught below decks in an air pocket could live for hours, even days, in the certain knowledge that there was no escape.

On the other hand, a cargo of logs might keep a badly damaged ship afloat. Ammunition ships could explode and vapourise the crew before they knew what happened. Oil tankers could stay afloat because oil is lighter than water. But oil can burn and there are many accounts of survivors abandoning a burning tanker only to be burned alive when the sea itself caught fire. Or of men being picked up out of the water, only to die in agony as their innards were burned by all the oil they had swallowed. The men at sea, living on their nerves, waiting for the slam of a torpedo, knew all about this.

And then there was the sea.

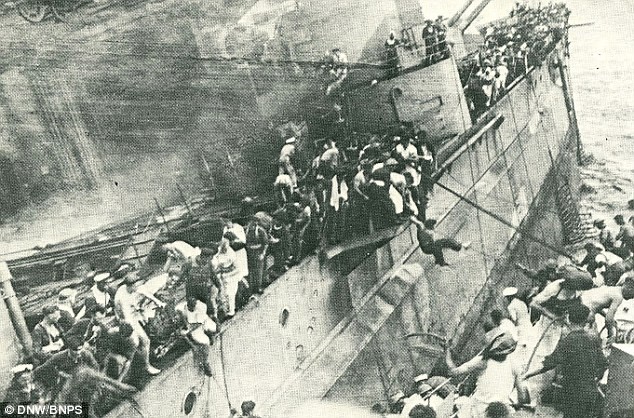

After the shock of being torpedoed, a survivor would, if he were lucky, find himself in a lifeboat. They were open boats, with sails and oars and no protection from the elements. Most held about thirty-two persons. The survival rate after a couple of days was grim, especially in the winter, in the North Atlantic or the Arctic. And there are many reports of men in lifeboats finding that the emergency rations had been stolen, something the port of Liverpool was notorious for. The Atlantic is a very big place. And very dangerous.

One account sticks in my mind, that of Chief Mate Stanley Simpson, whose ship was torpedoed off West Africa and who sailed the lifeboat 820 miles right across the Atlantic to Tobago. Remarkably, all twenty-two men on board survived (just).

After his ship was torpedoed and the order was given to abandon ship, together with a young apprentice, Simpson searched the ship to make sure that all who could get off did. They left her themselves just in time, and had to swim for the lifeboats, waiting some way off. Simpson’s report states:

“The boy seemed to be tiring and did not speak for a long while. His next words brought the sour metallic taste of fear to my mouth.

‘Oh Christ! A shark!’

I had known fear before, and was to know it often again, but never such an intensity of terror as at that moment. The sleek shark fin seemed to move very slowly through the water. The boy was by this time almost unconscious and vomiting feebly as I towed him towards the boats. There were now three sharks circling us and drawing closer, and the first attack had a nightmare illusion of slowness – no sudden quick rush, but a deliberate head-on approach of indescribable horror. I struck out with my free hand and felt the dreadful solidity of the shark’s head as it swirled past, grazing the skin from my arm and from waist to shoulder.

The boy was taken only ten feet from the boat. I did not see him go – a violent wrench as the body was torn from my grasp, a sudden rusty colour staining the sea, a confused memory of shouting men and flailing oars as I was dragged into the boat.”

And the final sting in the tail: once a merchant seaman’s ship was abandoned and he entered a lifeboat, his pay was stopped.

"These were the men... upon whom Great Britain called for a life-line during the years of war, and these were the men whose contract ended when the torpedo struck. For the owners had protected their profits to the very end; a seaman's wages ended when his ship went down, no matter where, how, or in what horror."

No cross marks the place where now we lie

What happened is known but to us

You asked, and we gave our lives to protect

Our land from the enemy curse

No Flanders Field where poppies blow;

No Gleaming Crosses, row on row;

No Unnamed Tomb for all to see

And pause -- and wonder who we might be

The Sailors’ Valhalla is where we lie

On the ocean bed, watching ships pass by

Sailing in safety now thru’ the waves

Often right over our sea-locked graves

We ask you just to remember us.