“The price of liberty is eternal vigilance.” —Thomas Jefferson

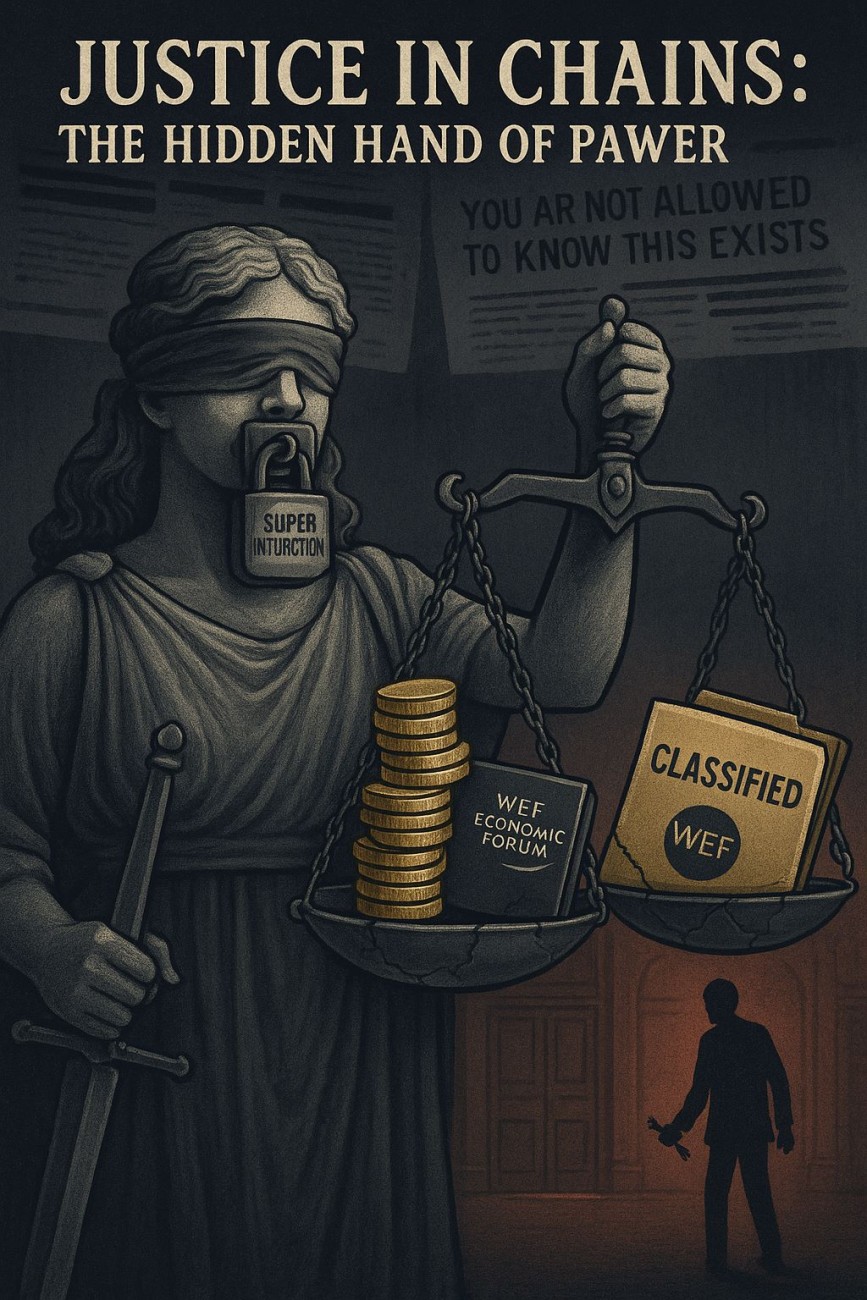

Even the most cynical of us were surprised and dismayed to learn that the British government resorted to a legal trick, the super-injunction, to hide their importation of tens of thousands of Afghans, including Taliban fighters into our – not their – country. Many concluded that British democracy and law is now a blatant sham, and very much at rock bottom.

Yet inn recent decades, the rise of super-injunctions in the English legal system has introduced a legal tool of astonishing power, opacity and constitutional consequence. These orders—judicial bans preventing not only the publication of information but even the disclosure that the injunction exists—pose a unique threat to the principles upon which democratic governance and the common law rest.

While they are sometimes portrayed as rare or used only in extreme cases to protect vulnerable individuals, super-injunctions have in practice been disproportionately available to the wealthy, the powerful, and the well-connected. And now, most disturbingly of all, the government. This creates not just inequality before the law, but a culture of legal elitism in which fundamental liberties such as open justice and freedom of expression are subverted behind closed courtroom doors.

This essay argues that super-injunctions represent a constitutional danger. They erode the principle of open justice, infringe upon the fundamental right to free expression, and introduce a covert form of censorship that bypasses democratic accountability. If left unchecked, they risk becoming a precursor to tyranny - a road which are far enough down already - a legal innovation that permits power to operate in the shadows, unchecked and unchallengeable.

The English legal tradition is anchored in the principle of open justice, the idea that justice must not only be done but must be seen to be done. This maxim ensures that judicial proceedings are transparent, accountable, and subject to public scrutiny. Courts are not temples of secrecy but public institutions answerable to the people. Or they should be.

This principle is not merely symbolic. Open courts allow for errors to be identified, abuses of power to be challenged, and precedents to be established in public view. They ensure that justice is not administered arbitrarily or in service of private interests. As Lord Chief Justice Hewart famously declared in R v Sussex Justices (1924), “Justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done.”

Super-injunctions represent a radical departure from this norm. They not only prohibit the publication of specific details about a case but also suppress any mention of the injunction’s existence. This is not simply a matter of privacy protection it is a tool of concealment. When courts operate under a veil of silence, the public cannot assess whether justice, and in the Afghan case government, is being properly administered, nor can journalists report on or question the use of such powers.

Even allowing for the egregious Afghan injunction, the danger lies not in any single super-injunction, but in their cumulative effect: the normalisation of secret justice, administered beyond the reach of the public eye.

The right to freedom of expression is enshrined in both domestic and international law. Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), to which the UK is a signatory, guarantees the right “to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority.” Super-injunctions amount to precisely such interference by stripping the press of the ability to report, and the public of the ability to know.

Unlike ordinary injunctions, which restrict the dissemination of specified information, super-injunctions go further by criminalising disclosure of the very fact that a restriction exists. This Kafkaesque framework creates a chilling effect across media institutions, prompting self-censorship even in cases where public interest demands disclosure, as the Afghan case most surely did. When legal silencing by government operates with impunity, it is not merely an erosion of journalistic freedom it is yet another step toward thought control – and we have far too many of those already.

In practical terms, this means a George Soros, Bill Gates, the WEF, Blackrock and, of course, the State can gag the press from reporting mass immigration, damaging Net Zero measures, grooming gang cases, gross negligence, even exposure of private misconduct with potential public consequences by politicians, all without accountability, without visibility, and without public challenge. Such powers are obviously inimical to a healthy democracy.

One of the most disconcerting aspects of super-injunctions is their unequal accessibility. Securing such orders often requires power, patronage, deep pockets, high-powered lawyers, and swift access to the upper echelons of the judiciary. For ordinary citizens facing reputational damage or threats to personal safety, such remedies are virtually unattainable.

This creates and cements a two-tiered legal system. The rich and powerful can pay for secrecy, while the rest must bear the burden of public accountability. It is no coincidence that the use of super-injunctions took off during the early 2010s in cases involving celebrities, bankers, footballers, and major corporations, figures and entities with both the means and motive to suppress stories that could tarnish their image or invite public backlash. And now government is getting in on the act.

In doing so it weaponises the court system to silence criticism and evade scrutiny. Privacy, once a shield for the vulnerable, becomes a sword wielded by the elite. The result is not justice but its perversion: a system that protects the powerful from the public, rather than the other way around.

The 2011 case involving a well-known footballer, who used a super-injunction to conceal an alleged affair, revealed the constitutional tensions such orders create. The injunction prohibited media outlets from naming the individual, until an MP, using parliamentary privilege, disclosed the name during a Commons session. But how likely is this when it is government itself that is the guilty party and Parliament is stuffed to the gills with cowards, fools, charlatans and globalist puppets? Not one MP stood up and used parliamentary privilege to expose the government’s Afghan people smuggling racket.

This episode exposed a broader truth: super-injunctions are not just legally questionable but politically explosive, raising the likelihood of tame, unelected judges curtailing speech in ways that circumvent democratic debate at the behest of the government. Parliamentary privilege exists precisely to prevent the silencing of elected representatives. But when courts grant anonymity in the name of privacy when Parliament turns a blind eye, a constitutional crisis looms. The judiciary's encroachment on the realm of political speech through super-injunctions risks undermining the separation of powers—a cornerstone of liberal democracy – and parliament’s apparent approval risks undermining the very foundations of democracy.

History teaches that tyranny rarely arrives all at once. It creeps in slowly, often under the guise of necessity. Censorship is justified as protection. Surveillance is sold as safety. And secrecy becomes policy. Super-injunctions, though framed as narrow legal instruments, possess the hallmarks of such creeping authoritarianism. They centralise power in the hands of judges and those who appoint and control them. They permit the suppression of truthful speech. They shield the powerful from the democratic consequences of their actions. In short, they introduce a secret legal mechanism that bypasses the public forum, and any legal tool that evades accountability is a danger to liberty.

As the UK gradually becomes a dictatorship, it is not immune to constitutional decay. The rise of executive overreach, the erosion of press independence, and the use of judicial orders to restrict public knowledge all point to a trend that should alarm defenders of freedom. Super-injunctions are not just a symptom of this decay; they are one of its tools.

The dangers posed by super-injunctions demands urgent attention. At the very least, strict statutory guidelines must be established to limit their use, define their duration, and mandate periodic judicial review. Public interest exemptions must be carved out clearly and applied robustly. The press must be granted the freedom to challenge such orders, and summaries should be published by default to ensure some level of transparency.

However, many legal scholars and civil liberties advocates argue that piecemeal reform is insufficient. The very concept of a super-injunction—secret justice by design—is so antithetical to the values of open society that abolition may be the only true safeguard. If the rule of law is to mean anything, it must operate in the light of day. No system of justice that demands silence can long remain just.

The legal system can be a guardian of liberty only when it is transparent, accountable, and open to challenge. Super-injunctions undermine all three. In the name of privacy and propriety and government convenience they introduce secrecy, censorship, and inequality. In doing so, they inch democratic societies toward authoritarian tendencies where truth is hidden, speech is controlled, and power operates without consequence.

As defenders of free expression, we must ask: Do we want a society where courts can silence speech with no public oversight? Do we want justice administered in secret, shielded from the people it is meant to serve?

If the answer is no, then super-injunctions must be confronted, challenged and, ultimately, abolished. Liberty cannot survive in silence.