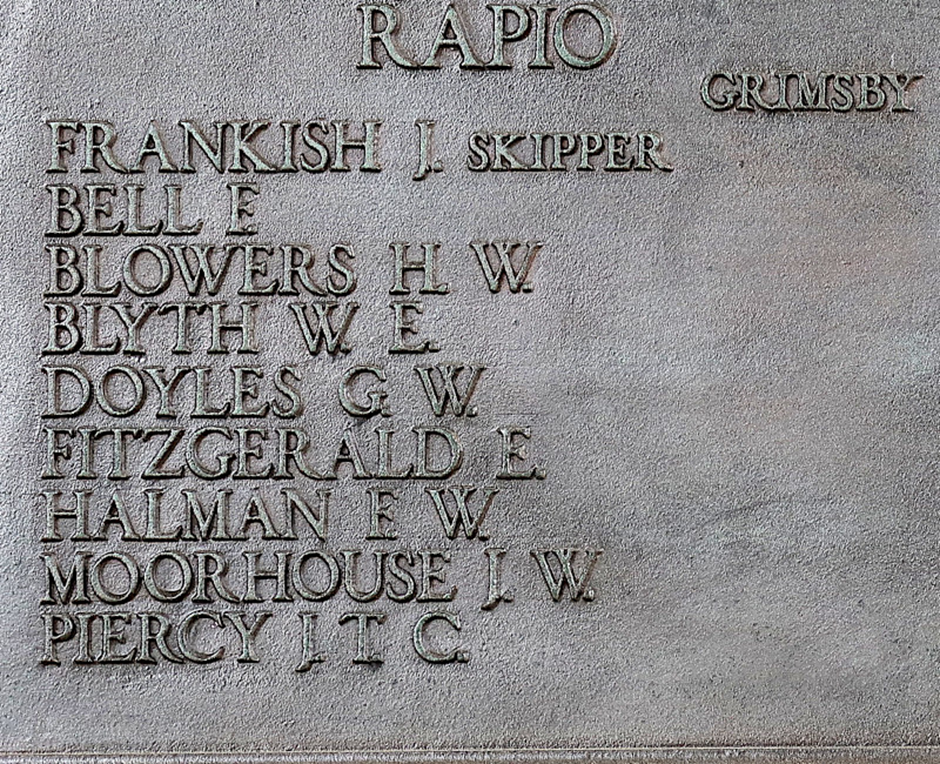

One plaque among many at Tower Hill Memorial, London

I have my wife to thank for providing many of the details for writing this article. In researching my ancestry, she discovered that my mum’s grandfather: John (Jack) Frankish was lost at sea, together with all his crew, as the skipper of the Grimsby trawler: Rapio (GY 400) during WW1.

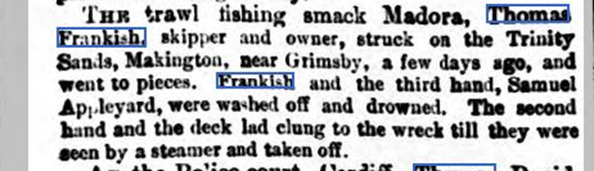

I had no idea that was how he died. Indeed, I never even knew I had relatives employed in the fishing industry. His brother Thomas was also lost at sea in 1882, as the skipper of Medora. (spelt ‘Madora’ in this newspaper article:

In the thirty-three years between those sinkings, Grimsby’s fishing fleet had transformed from sail driven wooden smacks to steel hulled propellered steamers. Initially coal fired, then oil. In 1886, Grimsby had eight hundred and twenty smacks. By 1902 there were four hundred-and fifty steamers, with no smacks which had become worthless. (1)

Amongst the ancestry evidence discovered by my wife was a PDF called: ‘Loss List of Grimsby Vessels 1800-1960’ complied by David Boswell in 1969 for East Lincolnshire Council. In reading it, I was shocked by the number of losses recorded in that document. I have now purchased the original booklet and in the introduction, David Boswell has revealed more details about under recording of lost vessels. Those that were requisitioned during the war by the Admiralty are included. Those that were purchased by the Admiralty before hostilities are not mentioned.

Small inshore fishing vessels of some three or four tons tend not to be mentioned in official records, and there are few references to them in local newspapers, so not all are in the list. Local newspapers never tended to report small craft losses, particularly if there was no loss of life. Towards the end of the 19 th century, the loss of lives in the fishing industry was so great (367 men and boys lost from Grimsby between January 1885 and December 1889) that the press tended to ignore those ships losses in which there was no deaths.

My great grandfather’s trawler was ‘lost’ on 8th February 1915. At the start of this process, I did not even realise the Germans targeted trawlers. Although some of those losses are recorded as “in Admiralty Service” Which usually meant they were used for mine clearing purposes. Albeit that was not shown against Rapio. Her wreck was discovered by divers in 1980, and they theorised that it had been sunk by shellfire. I will write an article on that wreck, if I discover more. I have since read that:

“Most of Grimsby’s trawlers were commandeered as minesweepers (as planned) and served off the British Isles generally, in the Mediterranean and at Gallipoli. Altogether 305 of them were lost to enemy action during the course of the war and Grimsby’s naval and RNR casualties totalled 375. The owners of these trawlers were given some compensation by the Admiralty both for their use and when they were lost…” (1)

The Naval Trawler is a concept for expeditiously converting a nation’s fishing boats and fishermen to military assets. England used trawlers to maintain control of seaward approaches to major harbours. No one knew these waters as well as local fishermen, and the trawler was the ship type these fishermen understood and could operate effectively without further instruction. The Royal Navy maintained a small inventory of trawlers in peacetime but requisitioned much larger numbers of civilian trawlers in wartime.

Mines were difficult to see and were very effective. The minesweepers had to ‘sweep’ the mines using wires, bring them to the surface then detonate them by firing at them.

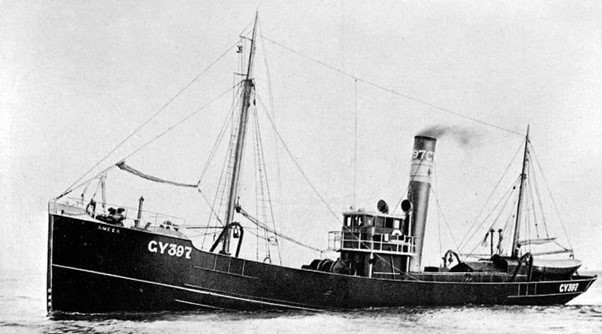

Grimsby trawler Ameer was equipped for minesweeping, with the addition of one 6 pounder gun. Ironically, she was sunk by a mine laid by a German submarine (UC 7) off the coast of Felixstowe on 18th March 1916. With eight of her crew killed.

Going through the Loss List document revealed some shocking statistics. Just looking at the period of the First World War reveals much:

Three days after the start of the war on 4th August 1914, the first Grimsby Vessel: Tubal Cain was sunk by the surface vessel Kaiser Wilhelm, 50 miles south of Iceland. Thereafter, during the course of the war, only one other vessel from Grimsby was sunk by the German Surface Squadron: Horus on 25th April 1916.

Within that same month of August 1914, Torpedo boats sank fourteen Grimsby ships in the North Sea. But the Torpedo boat contribution to the losses dropped off dramatically, with only another three vessels sank by them for the rest of the war.

The main antagonists were submarines (U-boats) with one hundred and fourteen Grimsby ships sank by them. The next lethal cause was mines, causing eighty-seven sinkings, with at least one mine that was believed to had been British laid.

Then there are the stranded, floundered, collisions or simply lost ships with no known cause, with ten further vessels lost in each of the following two years after the war and one in 1919 and two in 1920, confirmed from hitting mines. Those nine and eight losses annually outside of war, are a measure of how dangerous an occupation deep sea fishing was.

How David Boswell distinguishes causes remains a mystery. He never explained his sources.Enemy captains would probably have kept records of the vessels they sank, if they took the trouble to identify those details. But some of those U-boats were then sunk. I suspect survivors could determine a mine sinking cause. But losses of vessels such as Rapio with no survivors will remain a mystery.

Bear in mind this list is only vessels registered in Grimsby at the time of their loss. Ships which were salvaged are not included. Nor are ships which sailed from Grimsby, but which were not registered there at the time of their loss.

Though Grimsby was the largest of the UK fishing ports, imagine all the other fishing ports on the coast of the British Isles that have lost ships, especially during the time of war.

In the First World War—more than 17,000 people died and some 3,300 British and Empire-registered commercial vessels sunk as a result of enemy action. Losses in the Second World War were significantly higher, with 32,000 lives lost and 4,786 ships sunk.

The rules of engagement by the U-boats during the First World War are worth describing, as some of the Grimsby vessels sank had all the crew survive. The earlier practise was to implement the Prize regulations, which required that the U-boat surface, request to see the cargo or manifest if it were a merchant supply ship and then determine if they were going to sink it. If they were, they allowed the crew to take to the lifeboats and then sank the ship, using the U-boat gun. As torpedoes were unreliable, costly and limited in supply on the submarines.

An example of this was Grimsby deep sea trawler: Olearia (GY 331) stopped, then sank on 23rd May 1917 by UC 33. There were no reported casualties of the crew of the trawler.

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-u-boat-campaign-that-almost-broke-britain

In two single days: 28th June and 10th July 1914, six, then eight Grimsby vessels respectively were sunk by U-boats. On both days the sinkings were all in the same location.

https://www.benjidog.co.uk/Tower%20Hill/WW1%20Rapio%20to%20Red%20Rose.php

Other crew members were not so fortunate as the Olearia’s. Open the Benjidog link above and scroll down to the next vessel after the Rapio: Rappahannock also had no survivors, read the German government version of events.

These incidents were not isolated to the enemy: the crew of Q ship Baralong sank U 27 in August 1915 and were accused by Germany of carrying out atrocities. The Baralong went on to sink U 41 the following month. (3)

Combinations were tried in the early days of anti-submarine warfare with variable success. One of which was a trawler being tethered to a British submarine which had verbal communication via a telephone line alongside that tether to the sub. In the case of a German U-boat surfacing, the British submarine would engage it. This combination was successful in the summer of 1915, in sinking of two U-boats: U 40 sunk by submarine C 24 & trawler Tarnaki and U 23 sunk by C 27 and Princes Louise. (3)

Q ships

During the war, the British developed ‘Decoy Ships’ better known as ‘Q Ships’ These were effectively merchant vessels with hidden guns and hidden gun crews. Their purpose was to act as bait for the U- boats. These ships also carried additional ballast to be less likely to be sunk on being shelled/torpedoed. The gun crews were deployed as speedily as possible, as soon as the U-boat surfaced, to try and disable or sink it before it could identify the threat and resubmerge.

Q-ships were believed named after Queensferry in Ireland, where most of the modifications to the vessels were carried out. These included the addition of up to four hidden guns, and later depth charge and torpedo launchers. Gunnery crews were also hidden up, and had additional passages created within the vessel, so they could move around, without being observed as surplus non-fishing crew or merchant seamen. Around two hundred Q ships were produced.

Understandably after the British developed these tactics: U-boats were very cautious about surfacing to sink ships but usually had to with the limitations of torpedoes.

Q ships successes were not high, as in all they sank only twelve U-boats for a loss of twenty-five Q ships. British submarines sank sixteen. Entente surface ships sank thirty-six, with one hundred and twenty-three sunk by mines, accidents or unknown causes. U-boat development was in its infancy and mistakes in construction and operations often let to their sinkings.

Below is the crew list for the Rapio and this for me was when the sheer scale of tragedy hit home, not because of my great grandfather, but because of the addresses of their Next of Kin. Some of the crew lived very close to where I was brought up. I am familiar with those addresses. They all left those homes and families to earn a living and were never to be seen again

| Bell | Frederick | 46 | Second Hand | Husband Of Maria Bell, Of 95, Columbia Rd., Grimsby. Born in Grimsby. | |||||

| Blowers | Henry Walter | 31 | Trimmer | Son Of Walter Henry Blowers, Of North Pickenham Rd., Swaffham, Norfolk. Born in Spalding. | |||||

| Blyth | Walter Edwin | 34 | First Engineer | Husband Of Lily Bradbury Blyth, Of 66, Taylor St., New Cleethorpes. Born in Grimsby. | |||||

| Doyles | George William | 22 | Deck Hand | Husband Of Ellen Elizabeth Doyles, Of 80, Lord St., Grimsby. Born in Brigg. | |||||

| Fitzgerald | Edward | 47 | Third Hand | Husband Of Louisa Fitzgerald, Of 14, Rendel St., Grimsby. Born in Leith. | |||||

| Frankish | John | 47 | Skipper | Husband of Elizabeth Rendall Frankish, of 22 Mill Rd, New Cleethorpes. Born in Skipsea, Yorks. | |||||

| Halman | Frederick William | 30 | Deck Hand | Husband Of Ada Halman, Of 59, Mill Rd., Cleethorpes. Born in Grimsby. | |||||

| Moorhouse | John William | 43 | Second Engineer | Son of Mrs. Moverley, of Church St., South Kirkby, Wakefield. Born in Monk Bretton. | |||||

| Piercy | John Thomas Charles | 46 | Cook | Husband Of Louisa Piercy, Of 70, Freeston St., New Cleethorpes. Born In London. | |||||

The Tower Hill Memorial commemorates men and women of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets who died in both World Wars and who have no known grave.

https://www.cwgc.org/visit-us/find-cemeteries-memorials/cemetery-details/90002/tower-hill-memorial

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Benjidog Historical Research Resource for providing the photograph of the Rapio plaque, the Next of Kin names and addresses list for the crew. This has made the information provided by the CWGC much more accessible.

NB. If you see me referenced on the Rapio comments (website above) it is because I contacted Brian Watson, as strangely the Skipper (my relation) was the only crew member with no address or place of birth listed. Because of my wife’s hard work, I could provide hm with those details.

There is also a known recent issue with searching facility within that Benjidog website, that Brian is aware of, but he has other projects on the go and the fix could be some time.

I will write an article on the wreck of the Rapio, when I find more details. I am hoping to contact the divers: brothers Michael and Bill Woolford from Bridlington, if anyone should know them.

References:

David Boswell (1969) Loss List of Grimsby Vessels 1800-1960. For East Lincolnshire Council.

David Greentree (2014) Q SHIP vs U-BOAT, 1914-18. Osprey Publishing (3)

Peter Chapman (2002) Grimsby, The Story of the World’s Greatest Fishing Port. For The Breedon Books Publishing Company (1)

https://www.harwichanddovercourt.co.uk/warships/minesweepers(2)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_shipwrecks_in_1867 (which has no reference to the 12 Grimsby vessels lost in Dec (or Nov) 1867!)

Photographs of trawlers Olearia and Ameer copied from https://www.deepseatrawlers.co.uk

Editor’s Note:

Graham asked me to add a bit as I spent a few months on a trawler before joining the Merchant Navy proper, but in all honesty, I have little to add. I was only 16, and a mere deck boy, making the tea and sweeping up, and gutting and stowing fish. I hated it.

The trawler hand were the toughest bunch of men I have ever met, anywhere. Working on a trawler was several times more dangerous than working in a coal mine, and I remember being scared a lot, in heaving seas with nets, wires ropes and slippery fish all over the place. And of being cold and wet all the time. Trawlermen deserve our respect.

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/NHopAvs2XKQ

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/WPDrWcSL4LQ